Do you see that train-a-coming,

Oh, it's big old Ninety-nine;

Oh, she's puffing and a-blowing,

For you know she is behind.

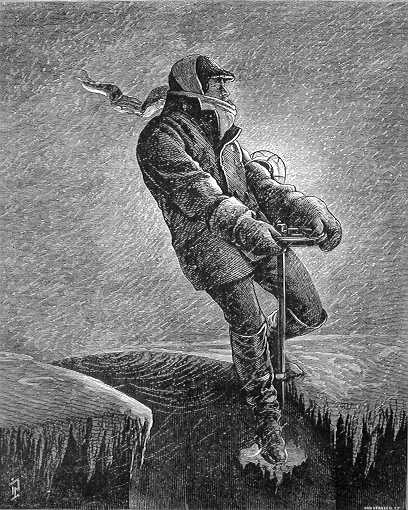

See that true and trembling brakeman,

As he signals to the cab;

There is but one chance for him,

And that is to grab.

See that true and trembling brakeman,

As the cars go rushing by;

If he miss that yellow freight car,

He is almost sure to die.

See that true and trembling brakeman,

As he falls beneath the train.

He had not one moment's warning,

Before he fell beneath the train.

See the brave young engineerman,

At the age of twenty-one;

Stepping down from upon his engine,

Crying, "Now what have I done!"

"Is it true I killed a brakeman,

Is it true that he is dying?

Lord, you know I tried to save him,

But I could not stop in time."

See the car wheels rolling o'er him,

O'er his mangled body 'n' head;

See his sister bending o'er him,

Crying, "Brother, are you dead?"

Sighing, "Sister, yes, I'm dying,

Going to a better shore;

Oh, my body's on a pathway,

I can never see no more.

"Sister, when you see my brother,

These few words to him I send;

Tell him never to venture braking,

If he does, his life will end."

These few words were sadly spoken,

Folding his arms across his breast;

And his heart now ceased beating,

And his eyes were closed in death.

The other two recorded deaths in Moonville are: Raymond Burritt, an 18-year-old killed in a mine explosion; and Charles Ferguson, who was killed in an interesting way while crossing the tracks: the train he was waiting on to pass snapped in two and he stepped out in front of the second half without looking in its direction.

Having someone take the time and put in the effort necessary to create such a transcendent piece of art, actually *using* my own words and the images from my website...well, "honored" isn't quite a strong enough word. I hope to speak with the person who made "Forgotten Ohio: The Ghost of the Moonville Tunnel" very soon, but whoever it is, I literally cannot thank you enough, nor can I express how flattered I am. I only wish I could produce something so cool.

For more information about the tunnel, visit the Herbert A. Wescott Memorial Library in McArthur, Ohio. They have an entire file dedicated to the subject. The "spook file" at the Ohio University library also contains some relevant material.

And, of course, be sure to check out one of the following Moonville-related websites:

The Moonville Cemetery

YouTube: Forgotten Ohio's Ghost of the Moonville Tunnel

YouTube: "The True and Trembling Brakeman" Performed by Tanya and Larry Rose

Ghost of Moonville

Ghosts of Ohio: The Moonville Tunnel

Athens News Article: "Ready For Some Different 'Haunted Athens' Stories? Read On."

The Troubadours of Divine Bliss: A band with a song called "Moonville Train"

Haunted Hocking Hills

Incidentally, if anyone has additional material about the tunnel, I would appreciate it if you would drop me a line.

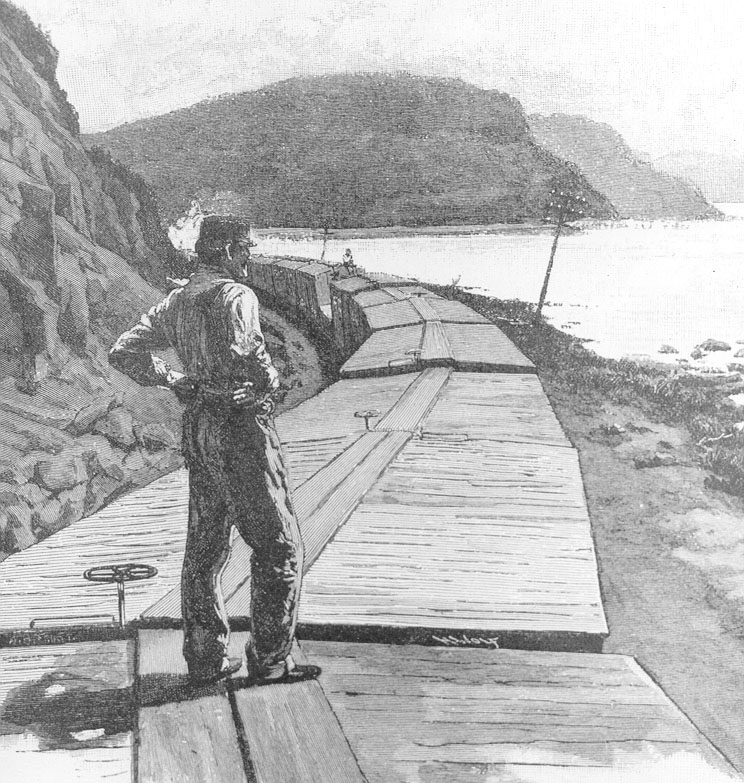

Clarke, Thomas Curtis. The American Railway: Its Construction, Development, Management, and Appliances. New York: Arno Press, 1976. [Reprint from 1897 ed.]

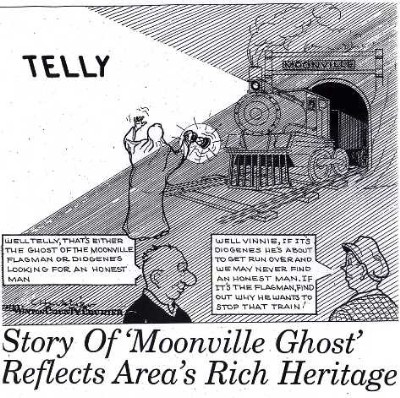

Cross, Roy. "Apparitions still at home in hills of Vinton County." Athens Messenger. October 31, 1993.

Everett, Lawrence. Ghosts, Spirits, and Legends of Southeastern Ohio. Haverford, PA: Infinity Publishing, 2002. pp. 23-26.

"The Freight-Train Brakeman." Harper's Weekly, March 10, 1877.

Gohlke, Christopher. "Ready for Some Different 'Haunted Athens' Stories? Read on." Athens News, Oct. 30, 2004. pp. 10.

Kalis, Nanette. "Haunted Athens." Athens News. October 28, 1993.

McArthur Democrat, March 31, 1859.

Vore, Bob & Bill Lawson. Nelsonville Nostalgia. 1973.