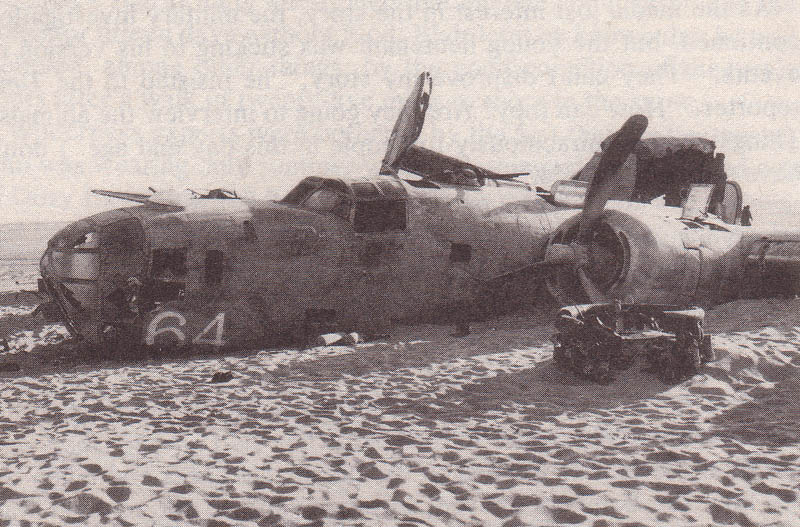

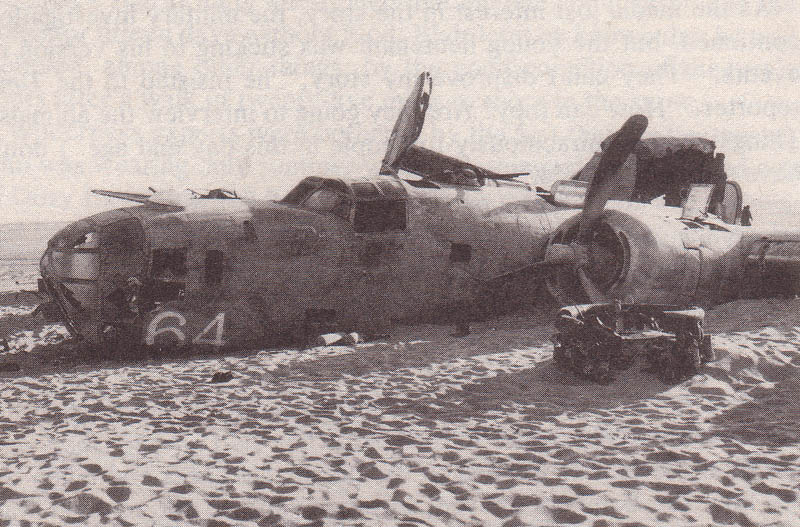

The fueslage of the Lady Be Good, found in the desert seventeen years after the crash.

According to Chris Woodyard, "The place is full of death. There are dead guys looking over my shoulder whenever I stop to look at something. I have to tell them, 'Go away, you're dead.'"

Interesting stuff. It makes you wonder if the Smithsonian is haunted. Or maybe the Holocaust Museum. I've been to both, and you have to figure the Holocaust Museum is a better candidate for haunting than an Air Force museum, but all I felt was an understandable depression. Below are the specific hauntings of the Air Force museum, taken mostly from Chris Woodyard's Haunted Ohio II.

A routine search was make at the time of the disappearance, and after the war more thorough searches were conducted along the Mediterranean coast, where it was presumed the bomber had gone down. When no traces were found, authorities concluded that the plane had crashed into the ocean.

In May of 1959, a British oil prospector came upon the Lady, crashed deep in the desert and eerily preserved by the dry air. The fuselage contained edible rations, canteens of potable water, and a Thermos of drinkable coffee. Fatigue uniforms and flight gear hung in their proper places, and guns and ammunition were carefully stowed. But there was no sign of the servicemen who had been on board. Further examination showed that the compass and one engine still worked. (American military technicians visited the crash site and removed the plane's instruments for further study.)

The following February another oil man, American James W. Backhaus, discovered the bones of five of the fliers. Along with the bodies were, among other things, a khaki sweater, a flight jacket, shoes, pieces of parachutes and harnesses, an empty canteen, and a diary that had been kept by one of the victims, Second Lieutenant Robert F. Toner. With it and the evidence in the fuselage, investigators were able to piece together the last days of the doomed men.

Eight of the nine men came down about fifteen miles from the crash site but did not search for the plane, presumably assuming it had been smashed to pieces or burned. A spent ammo clip indicates that they fired off rounds to rally together. (The ninth man, bombardier Second Lieutenant John S. Woravka, failed to join the others and was never seen again.) They then hiked northwest toward Benghazi, an impossible 450 miles away. The desert through which they walked was so arid and unsupportive of life that not even Bedouins visited the area.

They marched on, leaving in their wake markers, empty canteens, and shoes. By day they hid under parachutes to escape the sun and the 130-degree heat, and by night they walked. They rationed their water supply and took regular rest breaks. They crossed seventy miles of desert in a week.

The editors of Life magazine noted that

If there had been a way out this heroic effort would have saved them. There was none. The perverse fate which had made them miss their airbase held them to the end. For, unknowingly, they and the Lady Be Good had come down on a broad plateau in the midst of a vast expanse of desert which the Arabs know--and do not even enter on camel back--as the Sand Sea of Calanscio. They did, unbelievably, reach the dunes of the plateau's edge. Because the dunes there resemble those they had seen along the Mediterranean, they probably thought they had made it. The three strongest, Sergeants Moore, Shelley, and Ripslinger, went ahead for help. The rest, now too weak to walk, waited. They died, probably on April 12 when Toner made [the] last entry, eight days after the Lady had set out. The three men who went for help never returned. Their bones, like the wreck of the Lady Be Good herself, will probably lie forever in the desert.

The entries in Toner's diary are laconic; yet, written with a thick pencil, they tell with a simple eloquence the story of the airmen's last days:

Sunday, Apr. 4, 1943

Naples--28 places--things pretty well mixed up--got lost returning, out of gas, jumped, landed in desert at 2:00 in morning. no one badly hurt, cant find John, all others present.

Monday 5

Start walking N.W., still no John. a few rations, 1/2 canteen of water, 1 cap full per day. Sun fairly warm. Good breeze from N.W. Nite very cold. no sleep. Rested & walked.

Tuesday 6

Rested at 11:30, sun very warm. no breeze, spent P.M. in hell, no planes, etc. rested until 5:00 P.M. Walked & rested all nite. 15 min on, 5 off.

Wednesday, Apr. 7, 1943

Same routine, everyone getting weak, cant get very far, prayers all the time, again P.M. very warm, hell. Can't sleep. everyone sore from ground.

Thursday 8

Hit Sand Dunes, very miserable, good wind but continuous blowing of sand, every[one] now very weak, thought Sam & Moore were all done. La Motte eyes are gone, everyone else's eyes are bad. Still going N.W.

Friday 9

Shelly [sic], Rip, Moore separate & try to go for help, rest of us all very weak, eyes bad, not any travel, all want to die. still very little water. nites are about 35, good n wind, no shelter, 1 parachute left.

Saturday, Apr. 10, 1943

Still having prayer meetings for help. No sign of anything, a couple of birds; good wind from N. --Really weak now, cant walk. pains all over, still all want to die. Nites very cold. no sleep.

Sunday 11

Still waiting for help, still praying. eyes bad, lost all our wgt. aching all over, could make it if we had water; just enough left to put our tongues to, have hope for help very soon, no rest, still same place.

Monday 12

He went for his first night on the job. He met his supervisor there who explained to him that they have had a hard time keeping people on that shift, but my brother thought, "piece of cake." The first hour went by and everything had been fine. It was eerie already with the mannequins and old airplanes and all, but as he began to sweep he started seeing things out of the corner of his eye. He ignored them at first--or at least tried to! After half an hour of that he couldn't ignore it anymore, as ghostly figures began manifesting all around him: Pilots in their old flight suits, noises and voices, and even sounds of airplane engines.

My brother, who isn't afraid of anything, walked out of the best paying job that he's had in a long time in the middle of his shift. And vows never to step foot in that musuem ever again. When I asked what he had seen in there, he just simply replied that it's true when they say that a pilot never really leaves his plane!

No help yet, very cold nite

On May 15, 1960, two British oil prospectors found a sixth body. The identity of the dead man was not clear because two sets of papers were in the pockets of his uniform. One of these belonged to Technical Segeant Harold J. Ripslinger, the other to Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley. Whoever he was, he had walked thirty-eight miles after leaving Toner and the others, still on a northwesterly course toward the Mediterranean, and he died alone in the arid Sand Sea of Calanscio.

A reader of the website sent me this story, about her brother's experiences as a night-shift janitor at the Wright-Patterson museum:

My brother, who is a fairly large man and fears nothing, once got a job at USAF museum as a third shift janitor. He was all excited about the job; it was good pay and fairly easy work.

Woodyard, Chris. Haunted Ohio II. Beavercreek, OH: Kestrel Publications, 1992.