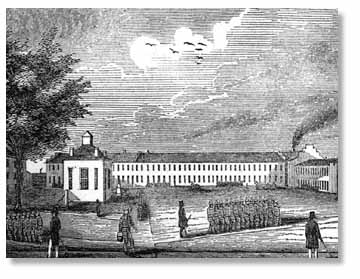

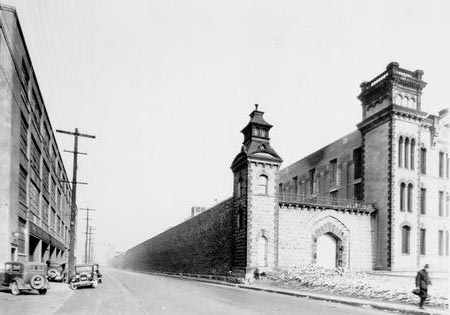

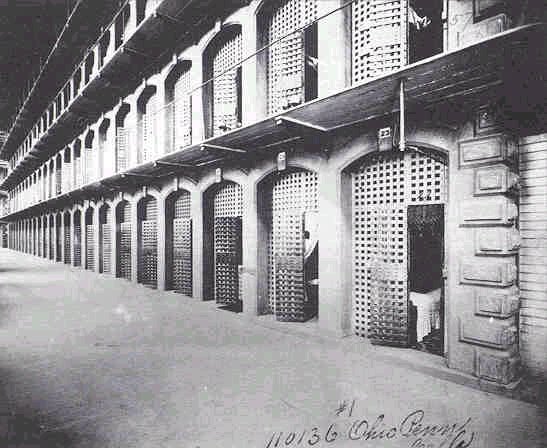

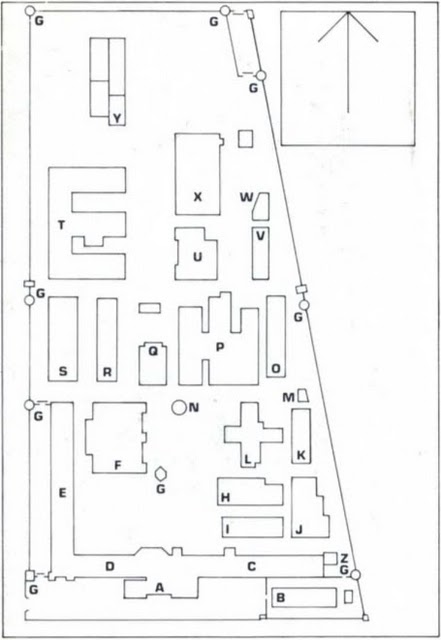

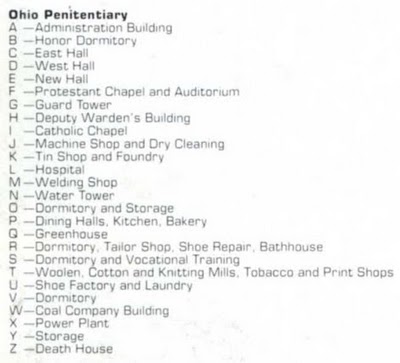

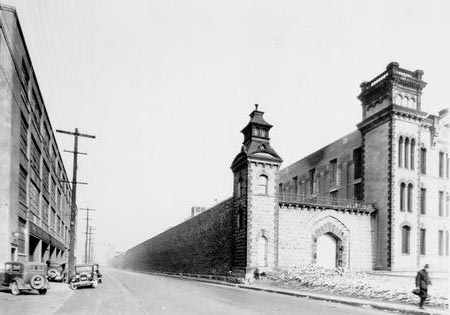

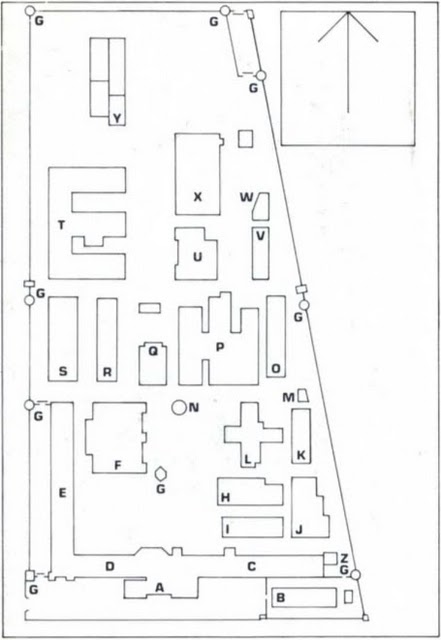

Perhaps the most impressive institutional building in the entire state, the old Ohio Penitentiary stood on Spring Street just west of downtown Columbus for 164 years, from 1834 until 1998.

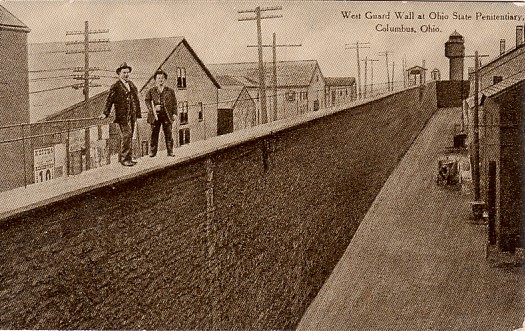

The first inmates who marched across the river from the original log-built prison in 1834 arrived at an edifice barely begun. A wall circumscribed the grounds, as it would until nearly the end of the following century. Inmates built their own stone cellhouses on the 22-acre site allocated along Spring Street at North Street. This included a separate facility for women, completed in 1837 within the main wall. Women were incarcerated here, separately within the same facility, until 1913, when the new women's prison opened at Marysville.

Not long after the original prisoners arrived the Pen began to grow rapidly, after a model established by Philadelphia's Eastern State. The prison was nearly as old as the new capital city. It was an era of prisons built in the middle of big cities--or what would become big cities. Columbus barely qualified as a city at all, but it was the planned and laid-out capital of Ohio, after Chillicothe and Zanesville had their turns. One of the first projects to make use of convict labor was the marble State House less than a mile away.

At that time the Ohio Penitentiary functioned as a federal and territorial prison as well; no federal prison system existed outside the use of state facilities. Ohio was a western state, and as such accepted many prisoners from the distant plains, deserts, mountains, and Pacific sea coast; inmates from the territories were brought in up the river or via roads and canals--then, later on, by train. A railroad bridge across the Scioto brought nearly all convicts directly to their new home.

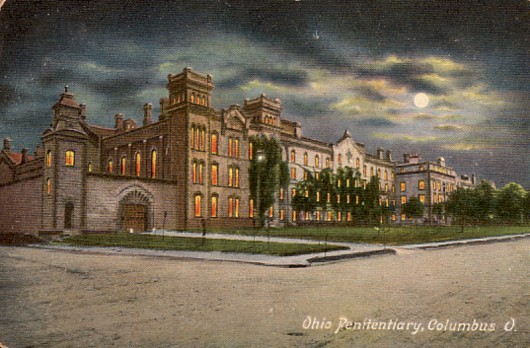

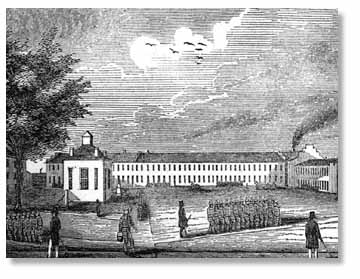

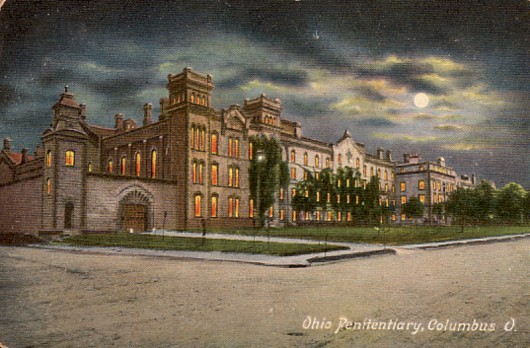

The Penitentiary's heyday was perhaps the years around 1900, when it was something of a tourist attraction, and held up as a "model" prison--largely due to the efforts of Warden E.G. Coffin (1896-1900). Coffin was a nationally recognized expert on penology; he traveled the nation touring jails and prisons and offering his expertise to state boards and panels of review. His speeches and essays were even published in book form, though how much of this was simply the result of rigorous self-promotion is hard to say.

Whichever it was, the Pen became a point of pride to the city and the state, and was featured in tours and sold on postcards. It remained a popular stop on tours of Columbus, as well as a major employer and a visual landmark of the riverfront and downtown. In 1908 it was described as the world's largest prison by H.M. Fogle. (His wonderful book on the prison, and its executed criminals, can be read by visiting my page about (and transcription of) Palace of Death.)

Not surprisingly, the reality of the Penitentiary was immensely different from the image civic leaders wanted to project--for the guards and superintendents as well as the convicts. Overcrowding was a problem nearly from the start. Disease ran rampant; rats and insects were ever present inhabitants, and the efficiency with which they conducted disease throughout the facility could be overwhelming. In 1849, for instance, a cholera epidemic burned through the prison, killing 121 in just a few short months. As long as it all stayed inside, and didn't affect the good citizens of the city, no one worried much about conditions behind the walls.

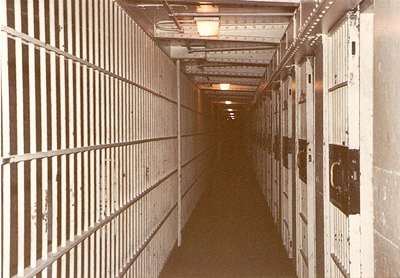

Built to hold 1,500 prisoners, the institution exceeded that number before even fifty years had passed. In 1893 a superintendent wrote of the wretched conditions for those incarcerated there at the time--all 1,900 of them. Bad though this is (overcrowding is a serious problem too often ignored or dismissed), it was nothing compared to what was to come. At its peak in 1955, the prison complex held 5,235 inmates--well over triple capacity and approaching quadruple.

Any prison that functions for so many years winds up housing some notable inmates. The Ohio Pen had its share--some famous, some notorious, some just weird or interesting. Here's a list of notable Ohio Penitentiary inmates in no particular order.

Guests of the State

-

John Hunt Morgan

-

Confederate cavalry general who led a "raid" north of the Ohio River; after his capture in Columbiana County he escaped from the Pen and fled back to the south. (More to come.)

-

James Brown

-

No, not the Godfather of Soul--though I can't help picturing him. This James Brown was a vampire...in a way. Really he was more of an interesting psychotic. In 1866 he was a sailor on an American vessel in the Indian Ocean when he murdered one of his shipmates and drank the guy's blood. Brown was placed under arrest by the captain, brought back to Massachusetts, and convicted of murder. In those enlightened days they didn't think much of insanity as a defense for any crime, even when it was so clearly the major factor involved--but then again, Jeffrey Dahmer couldn't get an insanity verdict in 1992, and he went much further. At any rate, vampire James Brown was a federal prisoner because of the nautical scene of his crime, and he wound up at the Ohio Penitentiary. Not much information is available about him beyond that, though it can probably be assumed that he gave up blood-drinking cold turkey.

-

O. Henry

-

The name William Sidney Porter doesn't ring many bells, but that's what famous short story writer O. Henry was known as when he became inmate #30664 in 1898. Porter was a federal prisoner from Texas. He was convicted of embezzlement (a crime he most likely didn't commit at all; an audit years after his time as a teller and bookkeeper at the First National Bank of Austin turned up discrepancies and they gladly laid the blame at his feet). He was already an experienced writer when he turned himself in and was admitted to the big house on March 25, 1898. Inside he worked as the night druggist (he was a licensed pharmacist) and got his own room, never having to live in the common cell block. One of the many stories he wrote at the Pen, "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking," was the first to bear the O. Henry pseudonym. He's best known for "The Gift of the Magi" and "The Ransom of Red Chief." The prison baseball field completed in 1970 was named O. Henry Field.

-

Chester Himes

-

Well-known black writer of the civil rights era. His work was infrequently political; mostly he wrote hard-boiled crime fiction and detective stories. Born in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909, he moved with his family to Pine Bluff, Arkansas--and then finally to Cleveland after a horrifying experience in the unreconstructed, racist South. (Gunpowder exploded in his brother's eyes during a school science experiment, and he was rushed to the nearest hospital, where a doctor refused to treat him--and possibly save his eyesight--because he was a black child at a whites-only emergency room.) After he was kicked out of OSU during his freshman year for playing a prank, things seemed to go downhill; he was arrested and convicted of armed robbery in 1928, and sent to the Ohio Pen to serve his 20-25 year sentence (incarceration and hard labor). Once there he found writing to be his best escape, a way to earn respect from guards and prisoners alike and also avoid violence. He started out with short stories, mainly published in something called The Bronzeman, then in 1934 made his first sale to Esquire. A close friendship with Langston Hughes opened some doors in the literary world, and helped him publish his best-known works: the novel If He Hollers Let Him Go, and the Harlem Detective series of violent, racially charged police mysteries (subsequently made into films such as Cotton Comes to Harlem and A Rage in Harlem). One of his early Esquire stories, "To What Red Hell" (1934), concerned the catastrophic 1930 fire at the Ohio Penitentiary.

-

Charles Makley and Harry Pierpont

-

Close friends and associates of John Dillinger. They participated extensively in his crime spree, robbing banks and shooting it out with the police. When Dillinger was arrested in 1933 and held in the county jail in Lima, Ohio, Makley and Pierpont (along with confederate Russell Clark) set out to free him. In the process, Pierpont fatally shot Allen County Sheriff Jesse Sarber. Apprehended in Tucson, Arizona, in January 1934, they were extradited to Indiana and then Ohio, where guilty verdicts were handed down. Both Makley and Pierpont were sentenced to die in the electric chair for their part in Sheriff Sarber's murder. They were transferred to Columbus on March 27, 1934, along with Clark, who had received a life sentence. But death row didn't suit the two partners, and they worked out an audacious escape. Taking a page from John Dillinger's book, Makley and Pierpont carved model guns from bars of soap, blackened them with shoe polish, and made a run for it on September 22. After assaulting a guard and trying to free Russell Clark (he chose to stay in his cell), they were confronted by guards with real, non-soap guns, and were gunned down in the corridor. Makley was killed; Pierpont was badly wounded, but survived to meet his end in Old Sparky at last on October 17.

-

Sam Sheppard

-

One of the most famous wrongful convictions in the long and storied history of American injustice is the case of Dr. Sam Sheppard. A respected citizen of Bay Village (a rich suburb just west of Cleveland) and a talented osteopath and neurosurgeon, he seemed about as unlikely a murder suspect as imaginable. But that's exactly what he became overnight in 1954. In the early morning hours of the Fourth of July, an unknown intruder (a "bushy-haired man") beat Dr. Sheppard unconscious (twice!)--and bludgeoned Marilyn Sheppard to death. Prosecutors had no interest in the bushy-haired man, instead deciding to pin the whole thing on Sam, who was thought to have sufficient motive because of an affair he was having with a nurse and Marilyn's recent pregnancy. The judge told columnist Dorothy Kilgallen before the trial that Sheppard was "guilty as hell," so he saw no reason to sequester the jury--this during a time when all the local newspapers were expressing similarly biased opinions on each day's front page. Predictably, on December 21, 1954 the jury returned a guilty verdict: Murder in the Second Degree, Life in Prison. Two and a half weeks after the verdict, Dr. Sheppard's mother shot herself in the head, and eleven days after that, his father died from a bleeding gastric ulcer. Dr. Sam Sheppard's luck only changed when he got a new lawyer, an up-and-comer named F. Lee Bailey who started to file intelligent, effective appeals. The court's bias, the failure to sequester, a near-total absence of blood spatter on Dr. Sheppard, specific injuries sustained by Marilyn and Sam, and an anomalous blood type present at the crime scene--all had been blithely overlooked. Once Bailey succeeded in getting a new trial (thanks in part to Earl Warren's Supreme Court, which upheld the decision to grant one), Sam Sheppard was found not guilty and freed. A corrrupt legal system had cost him ten full years of his life. Afterward he became a kind of celebrity; although the producers always denied it, the TV show The Fugitive (and later, the movie) was clearly based on his story. The major difference, of course, is that Dr. Richard Kimble (a doctor who awakens to an intruder in his home, is knocked out by him, and then finds that the man has killed his wife) escapes from the prison transport in a fluke accident and goes on the run to seek out the real killer. Nothing so cinematic happened to Sheppard. Also, the real killer in his case merely had "bushy hair," which is nowhere near as interesting as The Fugitive's one-armed man. (Incidentally, Mr. Bushy Hair has quite likely been identified. A convicted murderer named Richard Eberling, a handyman and window washer who worked for the doctor on occasion, boasted of the crime to fellow inmates and eventually confessed to Sheppard's son in 1993 when the son set out to clear his father's name for good. F. Lee Bailey, however, still believes a female neighbor responsible.)

-

James H. Snook

-

Executed after a very brief stay in 1930, Dr. James H. Snook was convicted of the murder of young Theora Hix. Snook was a professor at OSU and Hix was a student he had an affair with; once things went bad he drove her to the outskirts of the city and beat her to death with a hammer. The torrid details--particularly the sex stuff--made for a sensational trial, the saga of which is still fascinating reading.

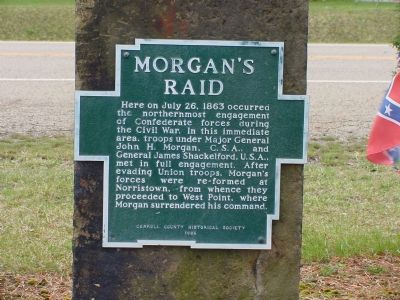

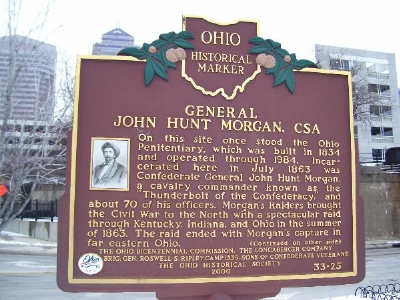

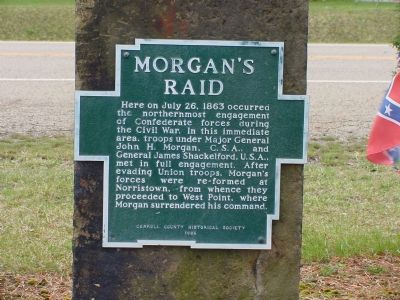

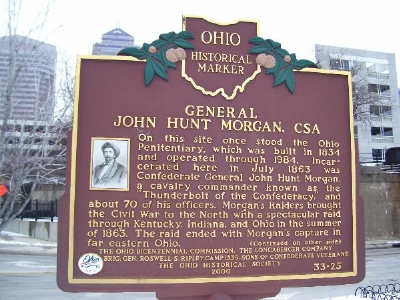

Morgan's Raiders

The Ohio Pen was used to house notable prisoners of the Civil War. While the majority in central Ohio were shunted off to Camp Chase, the walls and cells were thought necessary to confine Confederate General John Hunt Morgan and his officers, participants in Morgan's Raid. His "daring" (most historians tend to call it "foolish" these days) raid into Indiana and Ohio was sanctioned by no superior officer and accomplished nothing except to irritate and frighten rural northerners and reinforce Unionist views.

In the summer of 1863, hoping to divert Union resources around the time of the crucial battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Brig. Gen. John H. Morgan (an Alabaman by birth but a longtime resident of Lexington, KY) crossed the Ohio River without orders west of New Albany, Indiana, and rode across the southern part of the state. He engaged Home Guard soldiers at Corydon, killing five of them while losing eleven of his own men.

Crossing the state line north of Cincinnati, he marauded through rural south-central Ohio and made his way north into what is today Belmont County. Attempting to move into West Virginia on June 19, about 900 of his men encountered Union gunboats at Buffington Island and were decimated. Fewer than 200 escaped, including Mogan himself, while about 700 spent the remainder of the war as prisoners at Chicago's Camp Douglas.

On July 26, 1863, John Hunt Morgan and what remained of his command surrendered at a place in Columbiana County near Salineville or Lisbon (then called New Lisbon). This, the Ohio River at Buffington Island, and the location of a skirmish near Old Washington all occasionally claim to be the site of the "Northernmost Battle of the Civil War."

Morgan and several of his officers--including Confederate spy Thomas Hines--were incarcerated in the Ohio Penitentiary. As prisoners of war, and officers (though officers of a nation never recognized by ours, which has always confused the issue in my mind), they were treated surprisingly well. They were never assigned inmate numbers; were allowed to wear their own clothes; and guards addressed them by their military ranks--or even as "Sir," in Morgan's case. By all accounts Morgan and his men had an easy stay at the Pen--so easy that they cut it short by escaping.

Morgan and his men had broken through into a ventilation crawlspace which ran beneath the main block, and on the night of November 27, 1863, they escaped using a rope made of prison blankets and a bent poker rod. After midnight they boarded a train at the Columbus depot bound for Cincinnati, leaping off just before it reached its destination, where they would have been identified and re-arrested. They hired a small boat to reach Kentucky and were conducted south by sympathizers, eventually reaching Confederate territory again. Although "Morgan's Raid" (and his prison break and flight to safety) made big headlines and looms fairly large in history, it accomplished next to nothing, and was actually done in direct violation of General Braxton Bragg's standing order not to cross the Ohio River.

The 1930 Fire

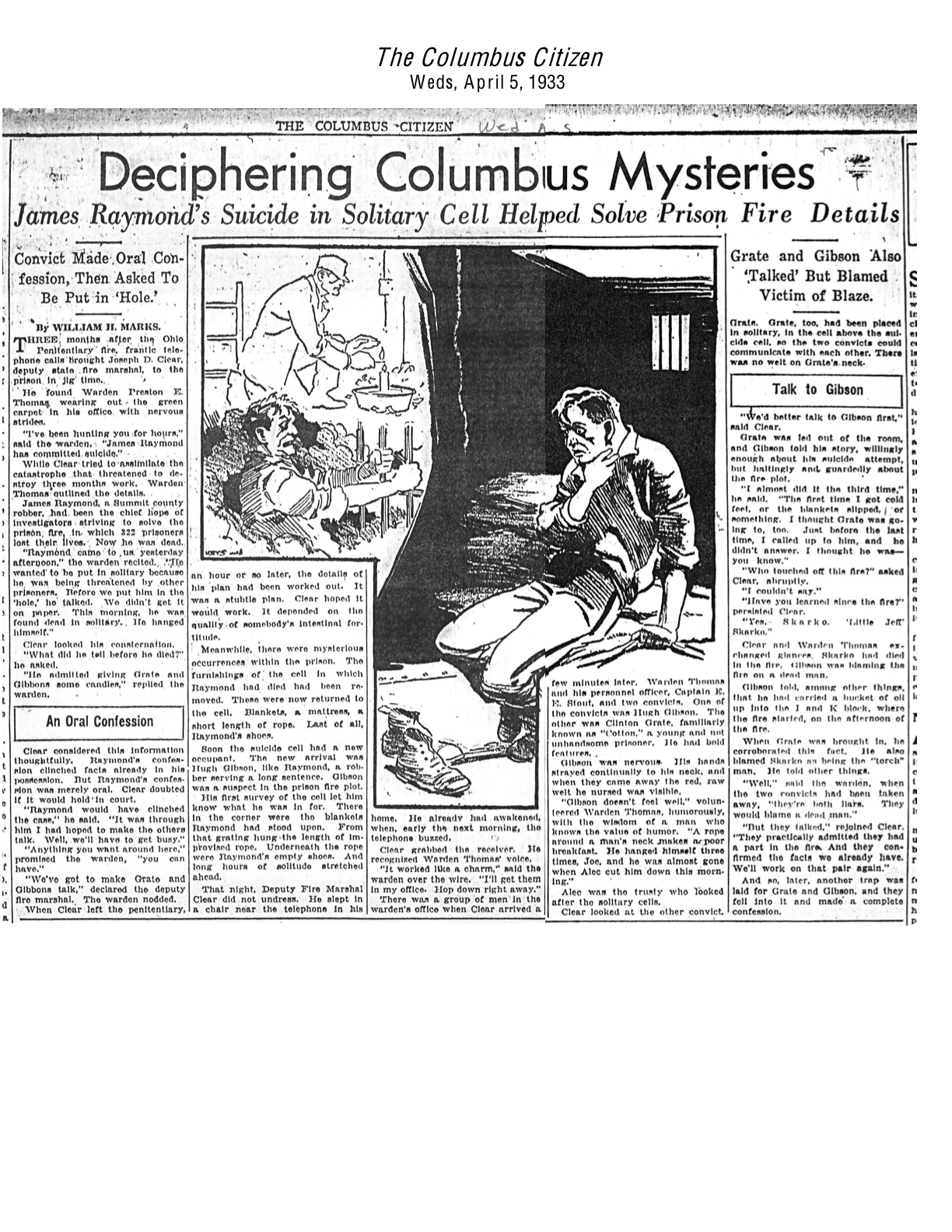

A botched escape attempt led to the deadliest fire in prison history on April 21, 1930. The final toll is given as 322 dead, although a thorough search of death certificates and records by the American Local History Network (at GenealogyBug.net) provides a complete list of victims of the fire, with death certificates, and it has only turned up 319. It's possible that the three conspirators are given as victims 320-322.

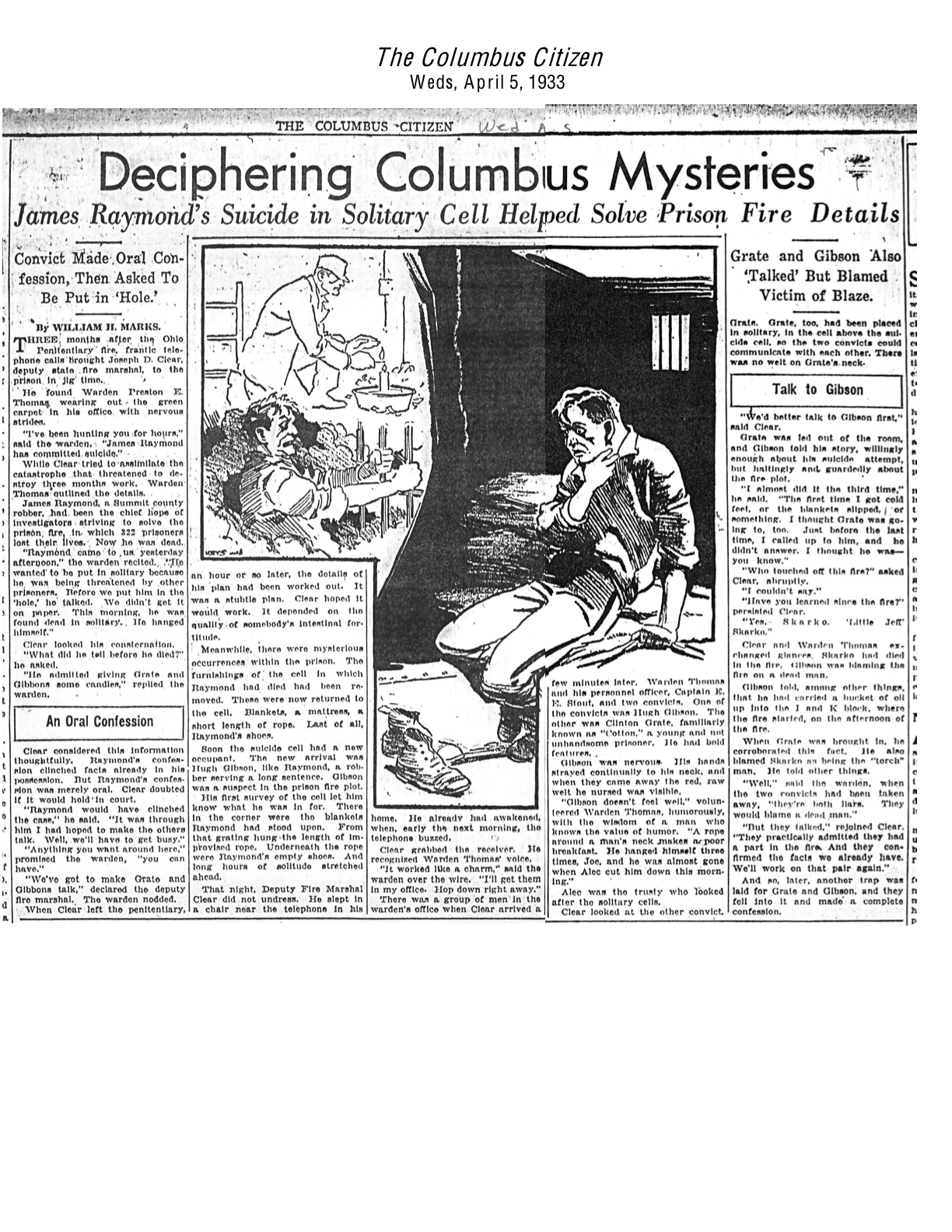

James Raymond's subsequent confession tells us how it happened. He and his two confederates, Clinton Grate and Hugh Gibbons, planned to set a fire in the roof of the cell block, which was under construction while it was rebuilt, and escape during the confusion. They placed a candle in a wide tray of kerosene and lit it. Their intention was for the flame to ignite the fuel, and thus begin the general fire, during the dinner hour, when the three of them (and most of the other convicts) were loose in the chow hall. But the device they rigged didn't ignite on schedule. Instead, it took about thirty minutes too long, and when flame finally started to spread, the inmates were securely locked back in their cells.

This was very bad news. More than confusion ensued when the half-completed roof caught fire. The area at the top of the block was as hot and dry as an attic, and was full of fresh lumber. A resin being used on the new wood was highly combustible. The work underway had generated mounds of sawdust, much of which floated in the air like pollen between grates to the fresh oxygen outside. When the kerosene caught, the entire new roof section essentially exploded.

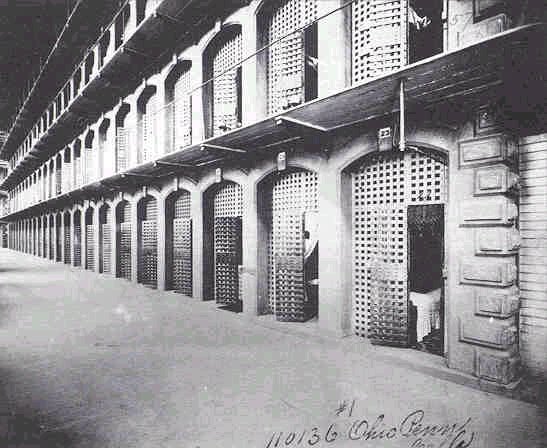

Flaming beams fell into the block, along with burning tar and roof tiles, and the prison building itself began to burn right away. Many deaths occurred because of oxygen deprivation and smoke inhalation, but the fire itself roared up and down the catwalks and roasted quite a number of convicts alive in their cells. At this time prisons used a turnkey system, requiring that each cell door be opened individually by a guard; there was no centralized emergency unlocking mechanism--not even a lever at the end of a row of cells to be thrown in an emergency.

Guards fought the flames as best they could and unlocked cell door after cell door, indiscriminately, and the main gates of the prison were flung wide. Guards enlisted prisoners as well, tossing them sets of keys so they could keep freeing as many inmates as possible. People carried each other out without regard for uniform (and many of the uniforms had been blackened or burned by the end of the night). One guard recalled being overcome by smoke and waking up with two convicts carrying him out to the lawn.

The circumstances surrounding the freeing of the inmates are sometimes recounted differently. Some claim that armed police brigades formed a perimeter around the grounds. But more often I've read that the life-or-death nature of the emergency served to equalize inmates, guards, and administrators. At least one convict died after going back in several times and carrying out men overcome by smoke. Prison employees recalled prisoners whose heroism saved lives, and several pardons were later granted based on their conduct. Perhaps most striking, there were no escape attempts amidst all the confusion; one inmate got lost downtown and turned himself in at a police station in the early morning hours. (The three who planned to escape had not intended to hurt anyone, and obviously changed their minds once things went wrong.)

After the fire department extinguished the flames, an eerie tableau replaced the hellish screams and smell of burning flesh. The destroyed blocks contained a great many cell doors which had never been reached or unlocked; the bodies strewn on the floors and walkways were greatly outnumbered by those of men who had died like animals tortured in a cage. The heat had literally cooked whole groups of inmates alive, while huge numbers had suffocated as the oxygen sucked away, or had choked on the toxic black smoke. Many corpses were found kneeling at the cell latrine, head in the toilet bowl with a wet towel draped across in a desperate bid for clean air. 130 other victims were severely injured.

Coffins were displayed to mourners at the State Fairgrounds, lined up row on row. It was a ghastly sight, but no mortuary could contain so many. Closed caskets were the rule that day.

James Raymond's conscience got the better of him; as the Columbus Citizen reported on April 5, 1933, he approached a guard, confessed his role in the tragedy, and demanded to be locked in solitary confinement. There he came clean, naming Clinton Grate and Hugh Gibbons, and asking for nothing even when the warden offered him anything he wanted in return for a signed statement. Then Raymond hung himself with bedsheets. Grate and Gibbons were convicted of second degree murder and each handed a life sentence. Grate then hung himself as well, after making his own confession. Gibbons lived on for years but barely spoke of the event; people who knew him said he was haunted by his role in the fire, and went to his grave broken by remorse.

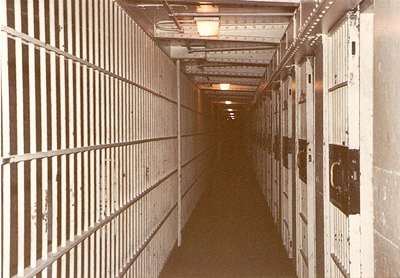

Like the fire at New York's Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, or Ohio's Collinwood School, the 1930 fire at the Ohio Penitentiary revolutionized the way prisons are constructed and run. In Collinwood, part of what changed about school buildings involved outward-opening doors with emergency bars; in prisons, entire blocks are now required to have a lever (and usually a button) which opens all cell doors at once, and a fire evacuation plan has to be in effect. Because overcrowding was such a factor in the high body count, several hundred inmates were transferred to a correctional farm in London--though overcrowding is one problem America's prisons have never seriously attempted to solve, as a glance at current statistics will show you.

The worst prison fire ever, it remains the third-deadliest structural fire in American history. Worse: Boston's Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in 1942 (492 dead); and Chicago's 1903 Iroquois Theater fire (more than 605).

Many of the bodies were shipped home, but there were dozens of unidentified and unidentifiable corpses. These unfortunate folks lie underground in the state cemetery near the intersection of Harper and McKinley, below I-70 on Columbus's west side. Their stones read simply UNKNOWN, row after row. And then there are the mass graves: burial pits dug for those so destroyed by flame that little more than ash remained; body parts, where they were found; and in a few cases, human bodies tangled together in desperate, inextricable embrace. The extra-large grave lots provided for those marked UNKNOWNS are the final resting place of the saddest remnants of that event nearly a century gone.

It's the fire--the most agonizing event in a place that saw a century and a half of agony--which is most often cited as the source of the ghostly manifestations at the Pen. The smell of smoke, sound of screams, and sight of spectral flames and burning figures were commonly reported thereafter.

The Riots

Two significant riots rocked the Ohio Penitentiary in the mid-twentieth century. The one most often overlooked in any short history of the Pen is the so-called "Halloween Riot" of 1952.

On October 31, 1952, prison officials lost control of the cafeterias, with inmates banging metal cups and plates rhythmically, and throwing food back and forth and at prison staff in particular. Some returned to their cells and elected not to take part, but the majority of those incarcerated had had enough and initiated a four-day takeover of the facility. The reason? It was simple enough: The food sucked! And apparently more than usual, because the demands were deadly serious. There were apparently no hostages taken, but inmates fought each other, set some fires, and broke into the infirmary for drugs (an old favorite). By November 3 all heat and utilities had been turned off, and no food was being delivered. A law enforcement conglomeration (Columbus PD, Ohio National Guard, State Police, and Department of Corrections) began to move in and engage in some kind of dialogue with a group of inmates crowded through a window. With communication nearly impossible, it took only the tiniest provocation for the assembled team to move in. When some of the inmates tossed pieces of porcelain or tile out at them, they opened fire, killing one prisoner outright and wounding four others. They retook the facility with minimal difficulty. There's no way to know whether the food ever improved. (My guess is no.)

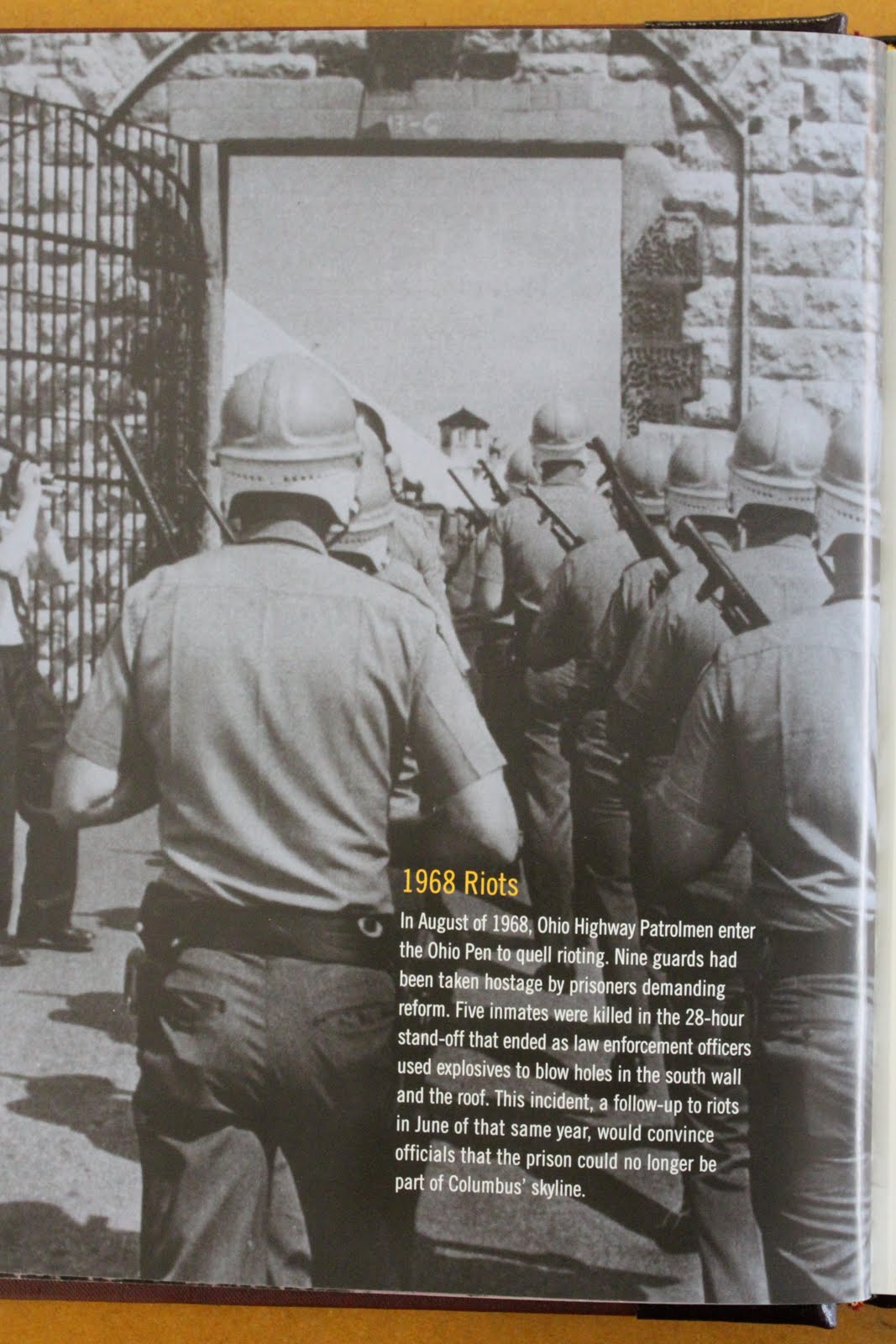

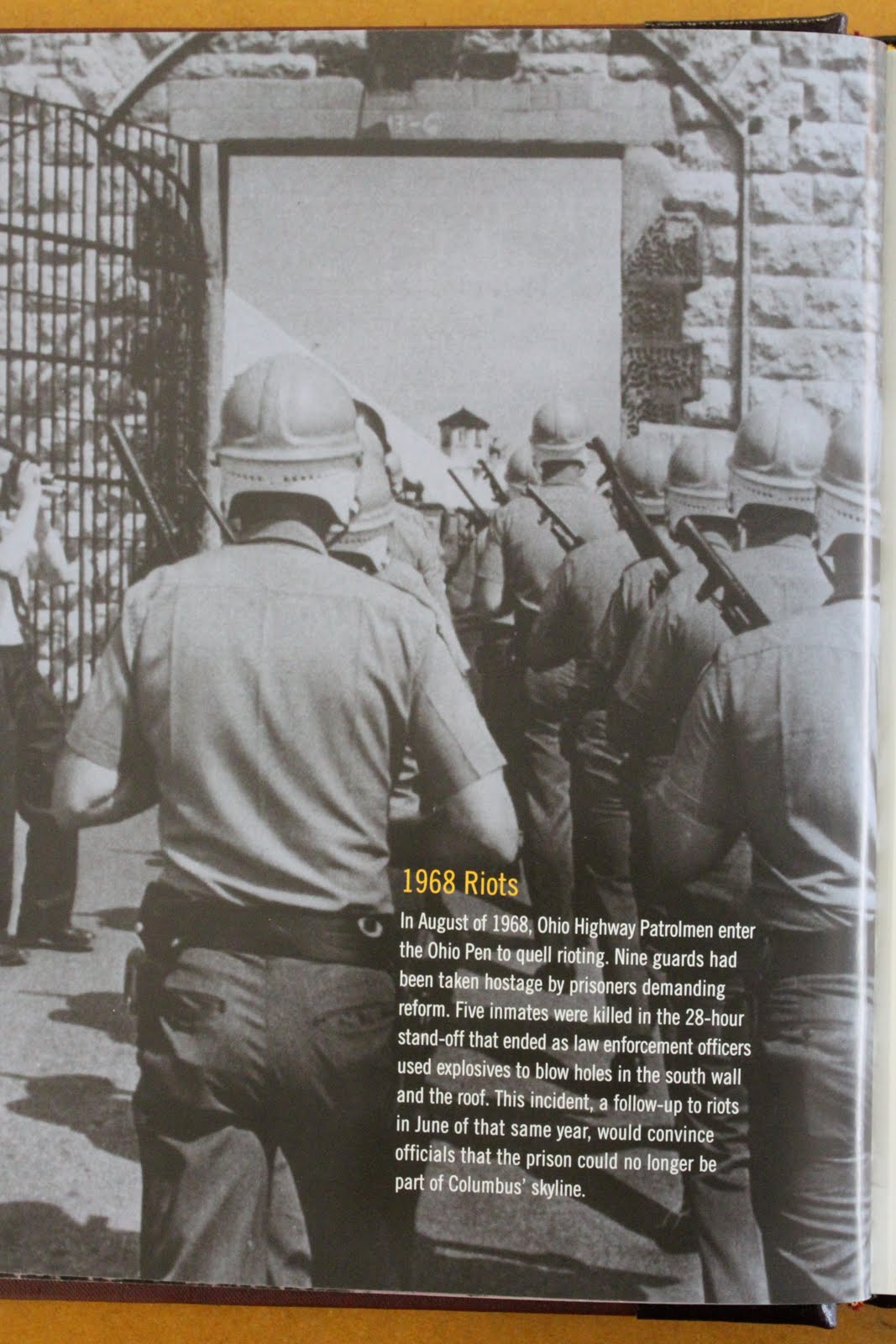

The 1968 riot was a far larger and deadlier affair. As before, it began in the cafeteria, but this time it was more than just inedible food that lit the fuse. Prisoners' rights are one of the forgotten causes of the 1960s era of protest and demonstration; a number of similar outbreaks occurred in prisons across America, culminating in the massive 1971 uprising at New York's Attica Correctional Facility. Once the Attica riot was quelled, 33 people were dead, including ten guards and prison employees. The riot in Columbus never reached that scale, but it was an intense two-day standoff that ended in violence.

That day--August 20, 1968--the mayhem spread from the cafeteria and into C and D blocks, which took the commissary, the hospital and drug dispensary (naturally), and set fire to other buildings. Later that day, holding nine guards hostage, the inmates issued a list of demands. They wanted certain guards fired; amnesty for the rioters; and a chance to speak to the media. The warden allowed them to speak to local news media, but disorder and violence among the assembled inmates led him to cut the press conference short.

The rioters grew more agitated through the night, threatening to burn the hostages alive; they said they would sever one guard's head if they weren't allowed to speak to reporters again. Authorities continued to refuse, all the while planning their attack on the occupied blocks.

The next day, an assault team (once again comprising state and city police, corrections officers, and National Guardsmen) assembled in full protective gear. At noon, a stabbing took place between two prisoners; officials witnessed it and gave the go-ahead, and around 12:50PM the assault team stormed the occupied wing of the penitentiary. To reach the hostage guards they blew a hole in the ceiling. The final cost of the riot incuded five dead inmates, as well as five more inmates and seven guards seriously injured.

Prison riots continue to occur on a regular basis; witness the 1993 takeover of Southern Ohio Correctional in Lucasville, Ohio. Part of the reason is that, unlike other civil rights issues brought to light in the 1960s, little to nothing has been done to improve prison conditions. A great many people are comfortable with the idea of any kind of indignity or pain being inflicted on a person who is incarcerated.

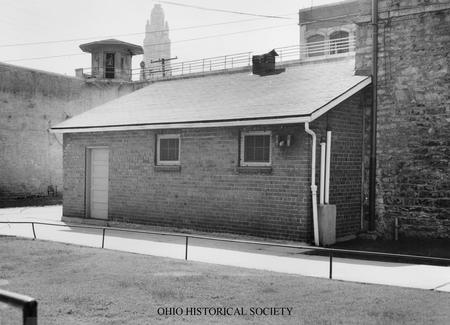

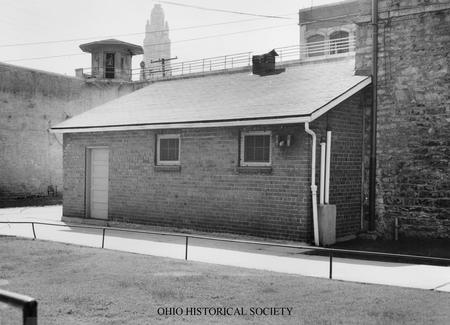

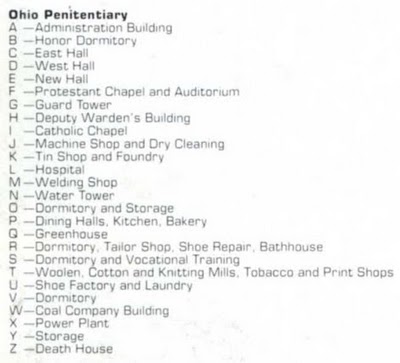

The Death House

Executions at the Pen are frequently mentioned as a source of the hauntings in the building. Between 1885 and 1963 there were 343 legally sanctioned executions at the Ohio Penitentiary. Twenty-eight were hangings; 315 were electrocutions. Three of the condemned were women. All of them took place in precisely the same spot in the Death House; when they retired the gallows, the electric chair was mounted directly beneath its trap door.

Photographs show the chair and the gallows trap directly above it. Less likely are some of the bits of death row folklore that grow up in every death penalty state. There's the one about the chair being built from the gallows wood; the tale of the carpenter trustee who eventually went to his death in the electric chair he built; the myth of the automatic pardon for anyone who survived the execution process, or did so three times. It is true that Ohio administered the second legal electrocution ever; the first was at New York's Auburn Prison, on August 6, 1890--by all accounts a gruesome event. Ohio, the second state to adopt the method, performed its first on April 21, 1897, running deadly current through a man named William Haas.

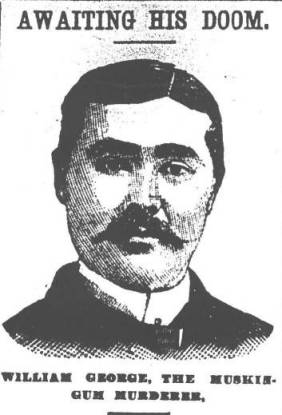

The Penitentiary was finished and had been in operation fifty years before legal executions were moved inside its walls. Before that, most hangings were carried out no more than a week from the day the judge passed sentence, and some happened within twenty-four hours. Most, however, were delayed long enough to allow people time to plan to come and see what were then public executions--"necktie parties" that were such a highlight of the social calendar. The authorities allowed the general public to witness the death of a condemned criminal in part to satisfy the legal preference for witnesses, and partially for the same reason parents brought their young children: to serve as deterrence, a lesson for those who might stray from the straight and narrow.

There was a religious aspect to the public hanging, an element of civic duty, and a public warning. But most of all it was a fair and a festival, a public exhibition with vendors cooking food and selling homemade crafts and telling fortunes; kids ran and played; musicians sometimes performed. All in preparation for the public executions. Sometimes crudely printed pamphlets were sold or handed out in the crowd, giving a time schedule of events, as well as brief details of the trial and a lurid description of the events surrounding the crime. It was a combination of bloodlust and boredom that brought families by the wagonful in from farms and crossroads villages sometimes a hundred miles distant, just to get a look at a dead man walking, as it were, up the steps onto the scaffolding and to view the expression on his face as the noose was pulled over his head and tightened just the right amount, with the knot in exactly the proper position behind an ear. Hands were tied behind the back, legs usually bound as well. At the appointed hour, after having been prayed with and given a last benediction by the clergyman of their faith, the condemned was permitted to offer last words. Prayers and exhortations of innocence were the most common, with the occasional warning to young men not to make the same mistakes he had and to steer clear of whiskey and loose women--which is still excellent advice. Last words generally spoken above the heads of a crowd gone silent for that very purpose.

Usually a hood was fitted over the head, but not always. Then a somber-faced court official (the executioner, who else?) would release the trap door, and the condemned would plummet through toward the ground, only to be jerked short, and then commence a violent death dance, arrested somewhat by rope tied around the legs. In many ways hanging can be considered the most humane way to have your government murder you; reports from the brink say the sudden tightening of the noose causes instantaneous blackout and an end to all consciousness, including pain. Hanging is a genuine science; the height, weight, and size of the condemned must be taken into account and the hanging rope measured accordingly. A rope properly measured snaps the neck between two upper vertebrae, killing instantly. Too short a rope and no one knows if the instant blackout happens, but the visuals are stomach-turning: the person chokes to death slowly, strangling audibly and kicking and swinging on the rope, seemingly clinging to life the whole time. And if the rope is too long, the head is simply pulled off the body. (This happened to outlaw "Black Jack" Ketchum in 1901 in New Mexico Territory; Black Jack was a member of the Hole in the Wall Gang made famous in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. But it happened to hundreds of others as well, and often spoiled spectators' enjoyment of the day's public hanging.) Interesting side note: Hangings, even when performed properly, are messy affairs. The bladder and bowels evacuate immediately, leaving a pile of wet shit. Most of the audience at a necktie party was too far back to notice, however, and most people still don't know that hangings (as well as many deaths in the electric chair) have this effect.

At any rate, until July 31, 1885, Ohio's legal executions were hangings conducted on courthouse lawns or specially designated spots. Ohio's capital city held its necktie parties at the southwest corner of Mound and Scioto Streets. Whole families traveled two or three counties on foot or by horse or buggy. As ghoulish as it sounds, watching someone hanged was pure entertainment, and not an everyday occurrence. They even took the condemned out of the State Pen to be killed. One example is a double hanging on February 9, 1844: William Clark and Esther Foster, both inmates of the ten-year-old Pen. William had killed a guard with an axe; Esther beat a fellow female prisoner to death with a shovel.

After June 1885 they moved the Mound Street gallows into the Penitentiary (not literally; most likely a new scaffold was built for each public hanging). Thus made private and given stricter protocols, the noose began to claim more victims. When Valentne Wagoner took the plunge in 1885 he became the first of many, many victims of Ohio's capital punishment statute. The last to hang was William Paul, on April 26, 1896. The first to die in Old Sparky was, as mentioned, William Haas, almost exactly one year later (April 21, 1897). The electric chair remained busy until 1963, when Donald Reinbolt became its 315th and final casualty. When executions resumed in Ohio it wasn't until 1999, when the Ohio Pen was just a memory and Death Row had long since been moved to Lucasville, and lethal injection tables had replaced gallows and electric chairs. It was in Lucasville that Wilford Berry, Jr. waived his remaining appeals and volunteered for his lethal injection. That was in 1999; since then Ohio has resumed executing prisoners with regularity.

Of the several books written about the Pen, most were written around the turn of the century--a time when the state took great pride in its large, modern prison. Most are a kind of survey of the facility and general description of its operations, and therefore not terribly compelling reading. But there is one exception: Palace of Death, a 1908 book by H.M. Fogle. Each chapter is about a different man executed in the Ohio Penitentiary's Death House. It offers an amazingly detailed report on the circumstances of the crime, the arrest, the trial, the sentence, the convict's time in prison--and, most dramatically, the execution itself. The first fifty-nine executions carried out at the Pen are detailed in chapters that read like short stories, made all the more interesting because the author didn't seem to have to worry about libel or the presumption of innocence. It's a fairly vicious book, as you might expect (and painfully racist), but it's utterly compelling reading. You can read more about it--and read entire chapters--by clicking here.

Palace of Death:

A True Tale of 59 Executed Murderers

Demolition

The Penitentiary was closed down in 1979 but stood empty for nearly twenty years, during which it was employed as a Halloween "haunted house" attraction--but not much more. It also enjoyed a reputation as the most notable haunted site in the city. The cavernous old prison was rumored to be layered with spirits from every conceivable source and era in its long history. The 315 people deliberately killed in the Annex, still pacing their Death Row cells or retracing their final walk. The 300+ dead in the fire of 1930, many of them roasted alive in their cells--men whose ghosts are said to howl and shriek, accompanied by a burning smell and phantom smoke. Suicides without number, still to be seen hanging from ceiling pipes or window bars. Countless stabbings and beatings, inmates killed by other inmates. Not to mention all the deaths from illness or old age, other causes.

In the mid-1990s my friend Rookie had the opportunity to infiltrate the place and look around. He described towering cell blocks, a flooded basement, a rack of keys, and paintings and murals done by the prisoners. He also said that it was possible to sit with your back against one wall of a cell and touch your feet to the other, which makes you think about what it must have been like to live out your life in such a room. Visit his page on it at Illicit Ohio.

The Columbus Landmarks Foundation finally took action to preserve the ruined prison in the mid-1990s, when it was clear that moneyed interests (mainly Nationwide) were eager to demolish it and develop the land. Shockingly, big money won the day, and after clearing a very few injunctions, demolition crews moved in and tore the place down in 1998.

Today this part of Spring Street is the Arena District, home to Nationwide Arena and Huntington Stadium. On the site of the main Penitentiary building you'll find the Arena Grand Movie Theater and a parking garage. I've heard that one wall of the theater's high-ceilinged lobby is an original, but I'm not sure. One thing has survived, however: the ghost stories. There are reports that Nationwide Arena is troubled by eerie sounds and spectral sights, including the ghostly echoes of the terrible prison fire. Some things just refuse to be forgotten.

Do you need to print out important information on your printer but need to

find discount prices on your ink?

Than go no further than Click Inks online! At Click Inks you can find affordable

cheap printer ink options! So don't get

caught low on your hp

ink cartridges or your epson

ink cartridges! Get your ink

needs all at Click Inks! Visit today!

Ohio Penitentiary Satellite Prison: Junction City

Ohio Penitentiary Satellite Prison: Roseville

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction: History of The Ohio Penitentiary

Ohio DRC: Capital Punishment in Ohio

Ohio History Central: Ohio Penitentiary

Illicit Ohio: The Big House - The Ohio Pen

Grave Addiction: Ohio Penitentiary

The Old Ohio Penitentiary: An OSU Group Research Project

Wikipedia: Ohio Penitentiary

Ohio Penitentiary.com

Wardens of the Ohio State Penitentiary

Ohio Executions, 1793-1963

1858 History of Franklin County, Ohio: Penitentiary

The Ohio Penitentiary Fire: A List of Victims

History.com: Prisoners Left to Burn in Ohio Fire

Ohio Prison Riot! British Pathe Newsreel

William George: Muskingum County Murderer

Back

Sources

Gall, Joe. "Motive." Journal of the Ohio Department of Mental Hygiene and Correction. November/December 1971.

Lore, David. "Inside the Pen." Columbus Dispatch. October 28, 1984.

Marks, William H. "Deciphering Columbus Mysteries." Columbus Citizen. April 5, 1933.

Smith, Robin. Columbus Ghosts. Worthington, OH: Emuses, Inc., 2002. pp. 67-72.